Does your mainsheet get knotted up at the most inconvenient time? Do you find it difficult to keep your boom out while going downwind? Do your feet get tangled up in your mainsheet while you are trying to tack? Here are some ideas that might help.

Mainsheet selection

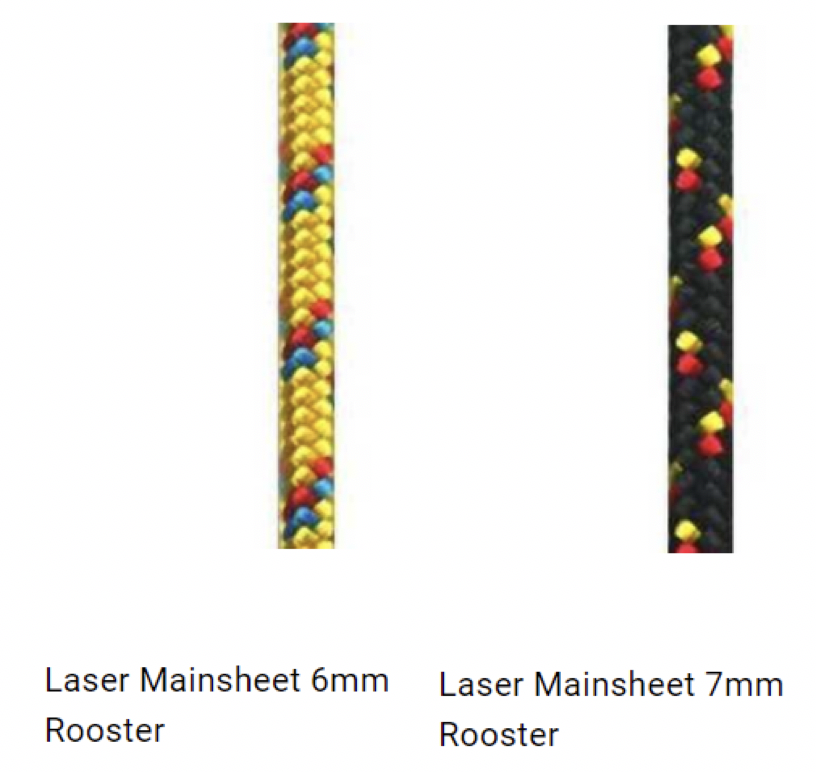

First, repurpose or throw away your old, fuzzy, heavy mainsheet. Replace it with either a 6- or 7-millimeter Rooster or equivalent mainsheet. The 6-millimeter Rooster yellow is used by most of the World Cup and Olympians in all conditions. It is perfect for light winds and will allow you to keep your boom out while going downwind in light winds. Heavier mainsheets tend to pull your boom in and make the sail collapse in lighter wind.

Rooster Mainsheet 6mm and 7mm

For heavier wind conditions, I like the 7-millimeter Rooster black because it puts less strain on my hands. Your mainsheet should be at least 44 feet long. DO NOT CUT IT SHORTER!

Mainsheet preparation and installation

Put your mainsheet in the washing machine and run it through a cycle or two to wash the shine off the mainsheet. This will make it less slippery and easier to grip. Al Sargent goes a few steps further and suggests, “When I first get a Rooster mainsheet, I like to wash it on extra hot to get out all the slippery coatings. Then I like to run it through sandpaper, maybe 100 grit, a few times so that it's slightly fuzzy and thus easier to grip. This extends the wind range in which I can use the thinner, yellow 6mm Rooster mainsheet.” He also suggests tossing your mainsheet into the wash regularly to ensure that it's free of salt or grime that can make it stiffer.

I like to put two figure-eight knots about a foot apart at the cockpit end of the mainsheet. The knots prevent the mainsheet from running out through the mainsheet block. Not having the mainsheet attached allows me to throw the trailing end of the mainsheet into the water and drag it behind the boat to remove twists. I can also adjust the second knot to shorten the mainsheet in very high winds to prevent me from accidently letting out too much mainsheet which can cause an immediate death roll. When the wind gets up beyond 15 knots, I generally move the second knot up the mainsheet so that there is at least 3 feet between the knots. When the wind is light, I move the knot back down the mainsheet so that there is about 1 foot between the knots.

As an alternative, some people like to attach their mainsheet to the stern end of their hiking strap. There are some advantages and disadvantages to this approach. I will leave it up to you which system you prefer.

Starting

In between races and/or at the beginning of each starting sequence, get all of the kinks and twists out of your mainsheet. Carefully stack your mainsheet slack into the back of your cockpit. By doing this you will at least have one time during the race when your mainsheet is perfectly organized.

Upwind

You should be using your mainsheet to control your sail shape. This is a dynamic process. You are continually sheeting in and out, even if it is only an inch or two. Consequently, don’t cleat your mainsheet into the deck cleats. If fact, get rid of the deck cleats. The vast majority of the top sailors don’t use them at all.

Tacking

Before you begin a tack, make sure that you free up an arm’s length of mainsheet and lay it on the deck or on your lap. This will ensure that you are not stepping on or getting tangled in the mainsheet during your tack. Even better, free up an arm’s length of mainsheet after every tack. This will ensure that you are always ready to tack at a moment’s notice.

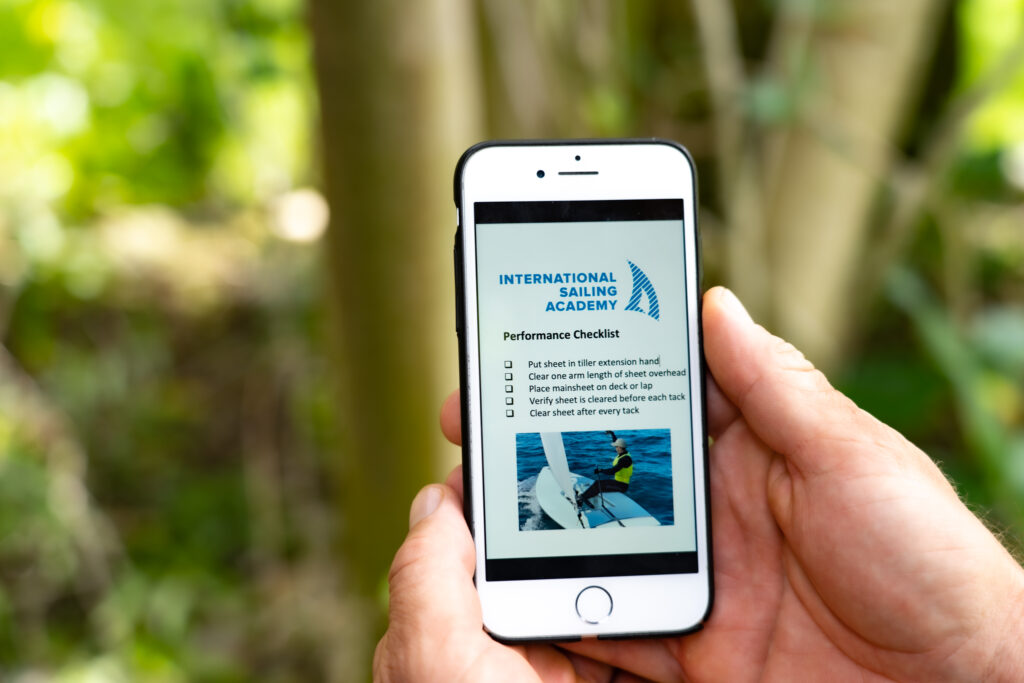

Clearing the mainsheet after a tacking in a Laser ILCA dinghy

Windward Mark Rounding

Free up a couple of arm lengths of mainsheet and lay them on the deck as you approach the windward mark. As you make the turn, raise your sheet hand with sheet in it high above your head and then drive your hand with the sheet toward the mainsheet block and then let the rest of the mainsheet slide through your hand. Do not loose contact with the mainsheet.

Downwind

Downwind sail trimming is also a dynamic process. You should be constantly trimming to find the precise by-the-lee angle that gives your sail the most power. This is constantly changing as your boat speeds up or slows down and as you change your sailing angle to achieve best VMG.

Leeward Mark Rounding

This is where you mess up your mainsheet the most. As you round the leeward mark you need to sheet in just as fast as you possibly can at the appropriate moment. You can practice building your speed and managing where your mainsheet lands in the cockpit on dry land in your boat with a partner. Start by sheeting in a fully extended sail and boom in slow motion to ensure that your hands and arms are moving correctly. Slowly build up your speed while maintaining correct form. With just a few days of practice you will increase your speed and improve your mainsheet management significantly.

Mainsheet Storage

When you put your boat away, don’t coil up and tie up your mainsheet. Or worse yet, don’t just pile it up into a tangled mess in your cockpit. Instead, lay it out flat on your deck from bow to stern and let it dry straight, with no kinks or knots. I maintain that if you let your mainsheet live most of its life straight, untwisted and untangled that it will be more likely to stay that way during a race. So far, I’ve had pretty good results with this approach.

If you have to coil up your mainsheet, Al Sargent and Tom Vollbrecht both recommend using a butterfly coil. This a technique that rock climbers use to coil up their ropes so they don't have kinks: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/How-to-coil-the-rope-?ActivityName=Multi-pitch-climbing

Good luck and sail fast, UNTANGLED!

I assume you are reading this because you want to improve your Laser sailing skills. Maybe you want to go faster. Maybe you want to win more races.

Whatever your motivation, to change your Laser sailing results, you'll have to change your Laser sailing habits. And, to change your habits, you'll have to follow the Cycle of Improvement.

Cycle of Improvement - International Sailing Academy

It all starts with Awareness – identify what you need to improve.

Then execute Deliberate Practice – repeatedly focus your conscious effort on the specific area you want to improve.

Convert to Habit – with practice, the effortful becomes automatic.

Repeat – begin again.

Your success or failure with the Cycle of Improvement hinges primarily on Deliberate Practice.

What is Deliberate Practice?

What is deliberate practice and how is it different from other forms of practice we have experienced?

Specific

Deliberate practice must be specific – often the more specific the better. For example, you may want to improve your tacks but we recommend an even more detailed level of specificity. For example, through video review, you determine that you're having trouble crossing through the cockpit. Then you determine that the position of your feet during a tack is different than the Olympic medalists' in a video you watched. Deliberate practice in this case would have you perform tacks with conscious effort focused on making sure your feet are in the correct position when you cross the cockpit.

Tom Slingsby Tacking Footwork

Repetition

Deliberate practice must include focused repetition. Use your on-the-water practice time very wisely to increase your learning rate. Each time you go sailing, execute as many repetitions of the new, specific behavior as possible. Be careful that you do not get overly fatigued to the point that you are practicing sloppy or wrong technique.

Feedback Loop

Deliberate practice must also contain assessment and feedback - a feedback loop. Without personal coaching, you'll need to implement a feedback loop yourself.

To do this, make sure you have a video of the model example of the Laser sailing skill or technique you're trying to emulate. Next, make sure you can identify and list the key actions that make that model better than what you are currently doing. Lastly, use a mental, digital, or paper checklist of those key actions to assess your performance each time you practice. While on the water and after your session, ask yourself: Did I do those things on my list? If not, which one(s) did I miss? What caused me to miss them? What can I do in my next attempt to ensure that I do those things?

Laser Sailing Performance Checklist

Digital Performance Checklist

Application to Laser Sailing Practice

Now we need to transfer the principles of deliberate practice to our specific Laser sailing needs. The key is to find creative ways to get in your focused repetitions (drills) of the specific techniques and skills that you need.

Land-Based Deliberate Practice (Simulations)

Both beginning airplane pilots and experienced airplane pilots spend a lot of time practicing with a simulator. Imagine how many more practice landings a pilot can get in with a simulator rather than actually landing a plane. Granted, the pilots still need to practice doing the real thing. However, the simulator gives them the opportunity to do many focused repetitions and to begin to create automatic habits.

This provides a good analogy for Laser sailors. Carefully analyze the skills that you need to improve. Can all or part of those skills be simulated somehow on shore? Can you practice all or part of the needed skills without a boat? For example, using a hiking bench? Can you practice all or part of the needed skills in a boat on a dolly?

Shore Based Drilling Repetition

If we can find an onshore simulation, we can get many more focused repetitions in before a sailor tires - and thus a foundation of new habits can be established earlier. Of course, they must also do the tasks on the water. The onshore simulations jump-start new skills, new habits, and sailing success.

On-the-Water Deliberate Practice

On-the-water deliberate practice sessions can be solo, with a group, or during your races. Each provides an opportunity for focused repetitive practice with feedback. The challenges come from the variables of wind, weather, and the very nature of sailing upwind and downwind.

Deliberate Practice Plan

Create a deliberate practice plan before each on-the-water session that considers weather and wind conditions. Also, rather than focusing on just one thing, it is best to break your practice session into logical sailing segments and focus on one or two things per segment.

Sailing segments might include:

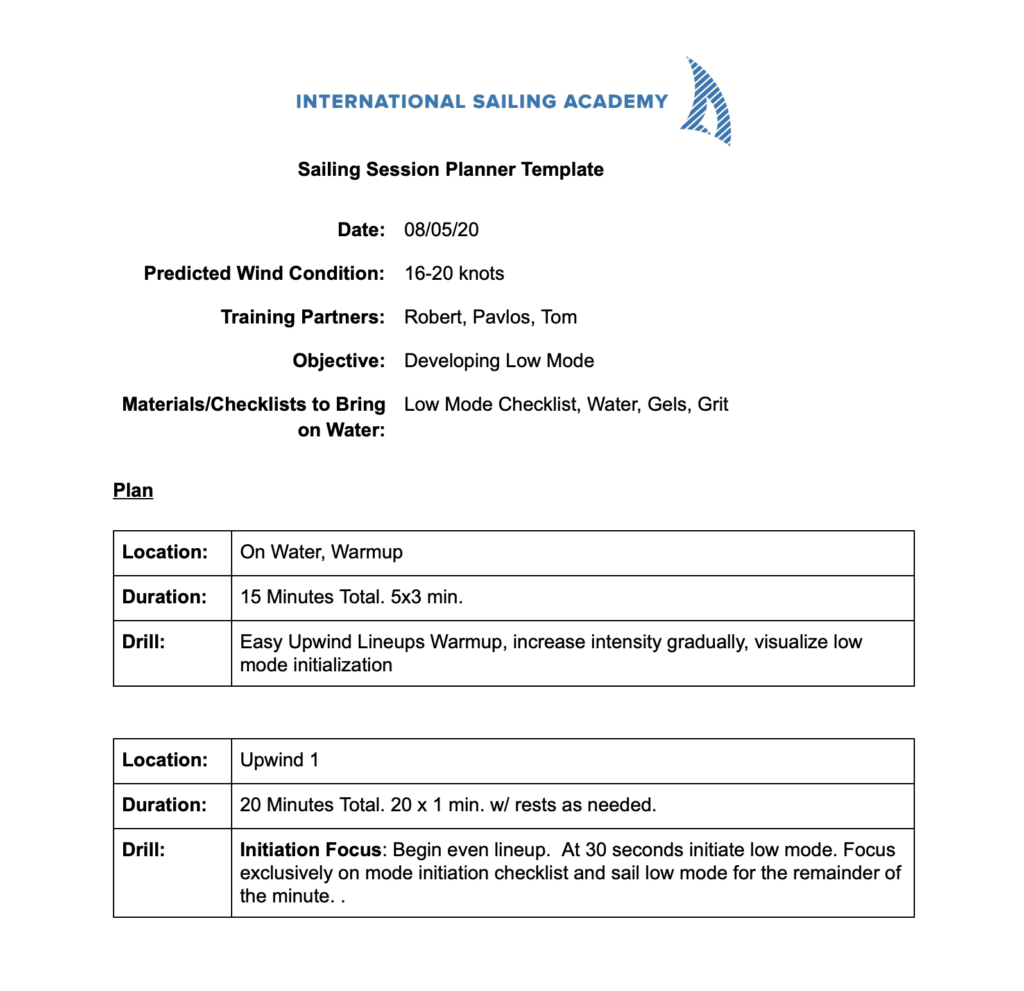

Note, a deliberate practice plan does not have to include all the sailing segments. Maybe it only includes one. A very narrowly focused plan might look like the below:

Deliberate Practice Session Plan

Note that the focus of the session is quite limited. It's often better to limit your plan to just a few items in just a few sailing segments, at least initially. As you get more comfortable with deliberate practice you may add some more items to your sessions.

Each of the skills/activities/drills should have a model and a specific aspect of that model that you are trying to emulate. Each time you perform, you will compare your performance with that of your model to get your feedback loop. Performance checklists are an excellent tool to help you with this.

"What looks like a talent gap is often a focus gap. The 'All Star' is often an average to above average performer who spends more time working on what is important and less time on distractions."

James Clear

It is extremely important that you do not fatigue yourself to the point that you are doing your focused repetitions incorrectly or sloppily. Make them perfect! At the same time, build your endurance so that you can also perform your new skills at the end of a race.

Drills Versus Racing

At some point, you need to effectively bring your new skills into racing. The best way to integrate new skills into racing is through a gradual increase of "pressure" from other boats. You add a bit of pressure to what you've just learned and see if you can still apply it. For example, at first work on your tacking footwork isolated from other boats so you're not distracted by them and can work at your own pace. Once you're happy with your progress, unite with other boats and practice some competitive tacking drills - this is a pressure increase that will help you integrate your new skill into "real life" racing situations. Then, participate in a practice race to further integrate the skill - your goal for the race may be to execute all your tacking footwork "the new way", even if the old way is still producing a better result - as is often the case during new skill development. Finally, execute the skill in real racing situations.

Changing the way you approach your Laser sailing sessions will improve your results. Follow the cycle of improvement and you will get better much faster. Don't follow it, and your growth will stagnate.

Note, you can approach your racing with a deliberate practice mindset as well - at least in your training races. Have a plan. Have models. Have feedback loops so that you can continually assess and improve during the race.

I remember an interview with the winner of the one of the World Cup Regattas. He maintained that he won because he was in the “flow” that allowed him to focus on the “minutiae” that makes a Laser go just a little bit faster. He felt that sailors who could maintain that focus without being distracted were the winning sailors. Perhaps, this is just a higher level of deliberate practice to which we can aspire if we use the principles and techniques described here.

Learn new Laser concepts and techniques with the International Sailing Academy Online Learning Series - and skyrocket your dinghy performance to the next level.