Originally published in Sailing World.

One rule of thumb is to ease your sheets when you're feeling slow, but the goal should be to never get slow. Here's how.

Getting to full speed can be simple, but maintaining that momentum is a different story. This much became apparent to me in my debut on the international Laser circuit. During one race at the European Championships in Estonia, I rounded the leeward gate ahead of a group. Another competitor rounded right behind me. He dove another couple of boat lengths to leeward until he had a clear lane below me, and within 30 seconds of choppy and gusty chaos, he sailed all the way in front of me and was starting to pinch me off.

Until that moment I had no idea it was possible to make so many mistakes in such a short distance, but the experience provided some pretty conclusive evidence that my biggest mistake came from having too much mainsheet tension at the wrong time.

Whether you’re sailing through a gust, lull, pinching, footing or through chop, knowing the proper time to ease your mainsheet can give you a big edge over those who are not. Here are five reasons why sheeting out can increase your upwind boat speed.

Sails require the airflow traveling to leeward of the sail to reach optimal sail force. Feeling and acknowledging this flow will allow you to stay focused on always trying to keep the backside of the sail working. When airflow detaches from the back of the sail, it is called stalling. One major indicator of stalling is when the leeward telltales fly straight up or forward. This happens after other parts of the sail have already stalled, however. Most commonly, the top quarter of your sail will stall first. By the time you’re visually aware of it, you will already have lost the sail’s optimal sailing angle.

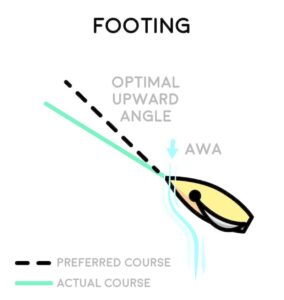

Ease When Footing: Sails require the airflow traveling to leeward of the sail to reach optimal sail force.

I often see this with people who like to foot, i.e., sailing slightly below closehauled. The windward and leeward telltales may look perfect, but other parts of the sail have already stalled. It’s a lot more common to see detachment in lighter conditions. The moment you see the leeward telltales not streaming across the sail, ease the sheet first to get the sails producing optimal force and attachment, then head up to your angle. Avoid stalling any part of your sail. For good measure, in my Laser, I like to see the windward telltale dancing downward about 50 percent of the time. This indicates that I am sailing high enough not to stall, but not so high that I am pinching.

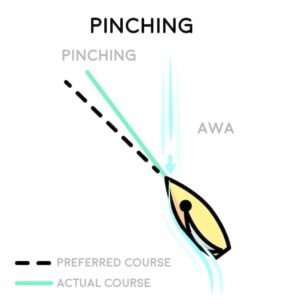

Suppose you sail into a header and are not quick enough to react. It doesn’t take long for the luffing at the front of your sail and the growing separation bubble on the luff to slow you down. All indicators point to pulling your sails in tighter to get rid of the luff, optimizing them for the higher angle. However, once you’ve established that your course is too high and make the adjustments back down to your optimal upwind angle, your boat speed is slower than a boat that never pinched. That pulls the apparent wind aft. Easing the sheet will momentarily relieve the stall induced by being slow. Then trim your sails to the new apparent-wind angle until you’re back up to speed.

Ease after pinch: Easing the sheet will momentarily relieve the stall induced by being slow.

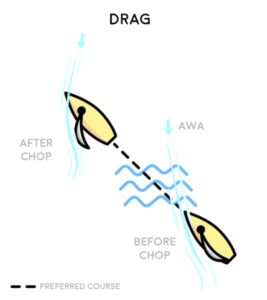

There are two components of drag when sailing; underwater drag from hull friction that can be increased by chop and swell, and drag that comes from a sail setup that is too deep and has excessive leach hook. Once your boat has reached top speed and your apparent wind moves forward, trimming your sails to have less leach hook will decrease drag in some conditions. In the moderate wind, it’s useful to keep the hook, as it helps to power through chop. In light wind, the impact of drag on the boat should slow it, causing the apparent wind to shift aft. By the time you notice the leeward telltale standing upright, the sails have stalled and have already realized a big loss in force.

Drag comes easy: Once your boat has reached top speed and your apparent wind moves forward, trimming your sails to have less leach hook will decrease drag in some conditions.

Sheeting out before the boat has slowed will maintain a force in the sails and help you stay at speed. In windier conditions, this stalling is perceived in the helm as a lift. Immediately following the impact of your bow hitting a wave, the apparent wind moving aft heels the boat and gives you the feeling of heading up. In bigger swells, it’s OK to steer up to keep your heel angle consistent. However, in most conditions, this extra weather helm is actually telling you that you have slowed and have the potential for more speed. Again, ease your mainsheet for the new apparent-wind direction is a crucial part of re-acceleration.

Properly easing the mainsheet into a gust can be the biggest contributor to improving your speed. When sailing into gusts there is a lot of feels, unlike sailing into lulls or sailing in light wind. Gusts are indicated by the heel. The boat heels up as true wind force increases and pulls the apparent wind aft. Resist the urge to treat this puff as a lift. It’s tempting to take the initial gains the breeze offers and point your nose closer to the wind instead of accelerating. However, no sooner will you reach the new apparent close-hauled course, then your sail will indicate pinching. An instantaneous pinch and return to the original course can be costly, especially since your speed is still relatively slow compared to the new wind strength. Instead, ease the main when the puff initially hits, thus trimming the sails to the new apparent-wind direction.

Ease in the gusts: Ease the main when the puff initially hits, thus trimming the sails to the new apparent-wind direction.

When sailing into a lull, your boat’s apparent wind moves forward. This is indicated by the sail luffing, windward telltales dancing or an obvious loss in power. You can see a lull coming by noticing the lighter shading on the water. A header would likely have a bigger impact on luffing the sail. In a header, bear away to maintain flow across the windward side of the sail, which instantly gives you more power. Don’t bear away in a lull. Your apparent wind will stay forward as you bear away, making it difficult to find more force in the sail, and easy to stall and sail extra distance. Typically, in boats that carry more momentum, you can sail into a lull and momentarily sheet on, blading the sail to reduce drag as your apparent wind moves forward. This option to ease your mainsheet will vary depending on what type of boat and how drastic the drop in wind velocity is. After slowing, the apparent wind shifts aft and requires a more forgiving sail setup that provides more power. On dinghies where mainsheet changes mast bend, sheet out to increase camber in the top of the sail. On boats where it affects leech twist, ease your mainsheet to open it increases the velocity across the leeward side of the top of the sail.

Speed in the lulls: In boats that carry more momentum, you can sail into a lull and momentarily sheet on, blading the sail to reduce drag as your apparent wind moves forward.

Stay active with ease your mainsheet, easing it for optimal sail force and apparent wind direction changes. The boat is most affected when these things are happening and we either don’t see them or are late to react.