In many conditions, we often see sailors with poor gust and/or lull response. In regards to hiking, particularly in gusts, there can be a tendency to “fight” the boat with hiking and often use too much steering to control power. We see the healing of the boat, pinching, corrective steers, and other issues in gusts and lulls. These issues often lead to unnecessary strain on sailors and reduced speed and VMG.

During lulls, even advanced sailors tend to chase apparent wind around obliterating VMG and slowing them down unnecessarily. Much is often said about changing gears in up and down pressure in regards to sailing shape, and while that’s very important, there’s a lot more to learn. By handling gusts and lulls efficiently, you’ll feel ease coming into the boat because you’ll be working with it, not against it, and you'll notice big performance improvements as well.

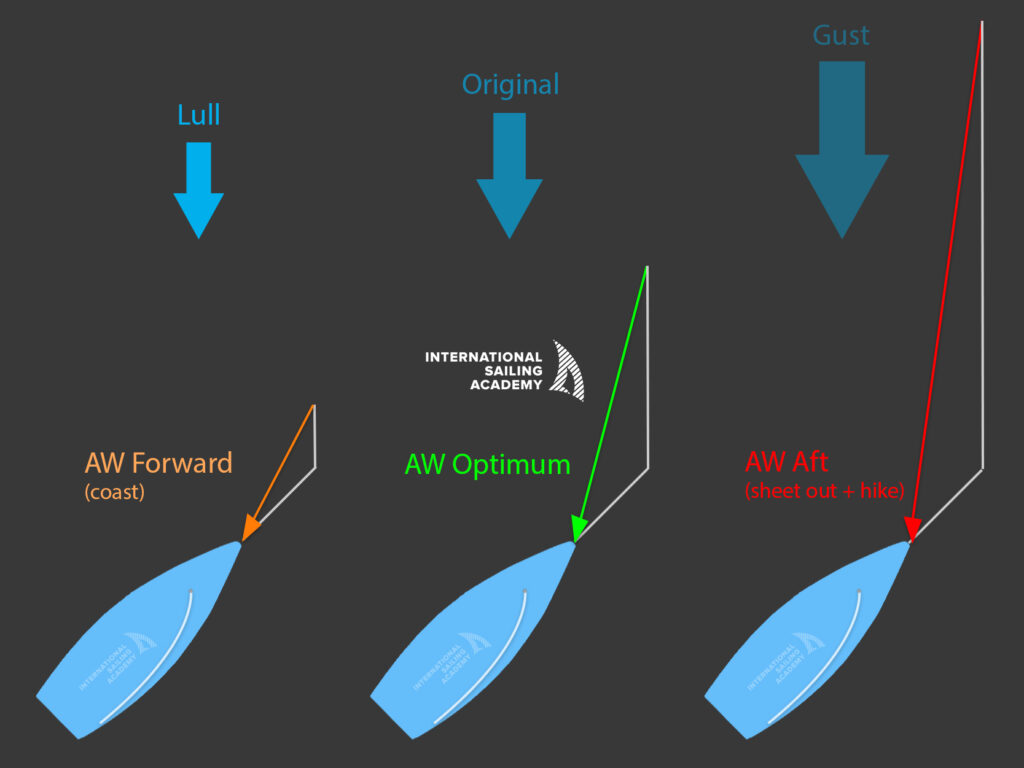

This diagram shows how your apparent wind is affected in the gusts and lulls before you decelerate or accelerate.

The Right Way

I don’t know who said it first, but it’s brilliant. “Ease, hike, trim”. This is the correct order of operations for handling a gust. Here’s why.

You’re sailing along and a gust approaches. Let’s assume for a minute, that the gust is from the same direction as the original wind direction - it’s just an increase in wind speed. At the moment it hits, your apparent wind instantly swings aft. As that happens, we want to achieve a few objectives:

I love Nathan Outteridge’s description of handling gusts in a 49er. He says “We let the onslaught of the gust rush past”. Sounds effortless right? If you think about more flow creating more lift, this really makes sense. We want to increase the speed of the airflow around the sail. The faster the flow, the more lift we get. We don’t want to allow so much force to enter the rig that the boat starts heeling up - that’s just creating sideways force and drag - and it’s tiring to hike against.

By accommodating our new apparent wind aft with sheeting out, we are able to increase flow on the sail and maintain a constant angle of heel.

We hike as much as is needed to do this - maximizing our hiking leverage if possible and sheeting out simultaneously to keep the boat heel angle the same. Complete these steps and your boat speed will instantly increase. If you’re familiar with target speeds, you’ll know that in a gust, you want to achieve your new target speed as quickly as possible instead of heading up and waiting, waiting, waiting for it to rise. Once this new speed is achieved, your apparent wind has moved forward again - so you’re able to sheet in to accommodate that. Have you changed the angle? No, because the wind has not changed direction.

In marginal hiking conditions, sometimes just adding weight in enough to instantly jump the boat speed up. In these cases, less or even no sheet release is necessary, because your apparent wind swings forward so quickly as you add weight that flow is not lost, and the heel of the boat is not affected by the gust.

The Wrong Way

“Pinch, Hike, Corrective Steer, Stall"

Due to the nature of gusts swinging the apparent wind aft, it’s easy to see why many sailors react poorly to the gusts and lulls. When your apparent wind comes back, weather helm is created and the boat naturally wants to head up. If you don’t let the sheet out and hike at the precise moment, some heel will be induced because of the increased rig load, and this creates even more helm. Telltales indicate that you “need” to head up, so, why not? Heading up seems and feels like a good idea for two reasons:

There is a sense when we feather/pinch that VMG is increasing. This is a false gain and is very deceptive. You’ve "pointed high" and you even have decent flow… but it’s only momentary, and you haven’t increased speed yet in the gust. Slowly, you’ll speed up to the new target speed to match the new higher wind speed. But, as this happens, your apparent wind is now moving forward again. Looking at your telltales, now it seems like you’re getting headed!

Sign up for a Laser Speed Week

At this point, flow is compromised and telltales request you to bear away - you’re forced to make a “corrective steer” back down to the original angle. Every corrective steer you make actually decreases flow over your sail and foils. In this scenario, the seemingly free ride up to a higher angle cost us speed (the speed that was reached almost instantly by those who were able to sheet out in the gust) and was eventually disastrous to flow as we came down.

It’s true that strong pointing is absolutely achieved through higher speeds first, not steering angle changes. The increased speed and flow over the sails and foils create more lift and this means less sideways force - and good pointing is actually a reduction of leeway. When you’re pointing well through good speed, apparent wind is forward and hiking is easier. So we do NOT want to feather or pinch up in gusts to manage them because it’s not really giving us better pointing/leeway reduction, just the opposite. Think about increasing flow and speed - ease, hike, trim.

Gust with Shift Components

What happens when the direction of the wind actually changes? What if it’s a gust AND a shift? This is actually pretty common in “fanning” type puffs that spread out from the middle, typical in offshore breezes. Depending on where you are on the radius of the puff, you’ll get a different wind direction. If you’re on the lifted side, it will feel just like a “normal" gust and your reaction should be the same. Ease, hike, trim -and then come up once you’ve accelerated.

If you’re in a gust with a header component, it will be clear instantly because instead of your AW moving back, it will slam forward and you’ll see your windward telltales come up. Try to anticipate this and just sheet out and steer down quickly to angle.

The Right Way - Coasting

I’m not sure that good lull response makes hiking easier, but it can be one of the few instances where we can accept a momentary “break” from hiking. The strategy when sailing into a lull is…. COAST. When you sail into a lull, your apparent wind slams forward, just the opposite of a gust. In this case, we want to: unweight, coast and decrease speed. Just like in a gust, we don’t want the boat to “feel” the lull- it’s an angle of the heel should not be affected. So this typically means that you’ll need to shuffle your weight inboard or just bring your shoulders up depending on the amount of wind decrease. From there, we need to deal with our apparent wind forward issue. This is one of the only moments in laser sailing where we accept poor flow as the best course of action.

The same as in gust response, we need to achieve our new target speed first. So we basically need to slow down - and while we’re slowing down, we might as well keep our height. So we coast.

You can experiment with trimming in tighter to various degrees at this point to reduce drag with the AW forward or alternatively you can ease a bit to keep some power and minimize stall risk. From there, as you slow down, AW is coming back, so we need to start easing again through that change if you haven’t already, until AW is at the optimum angle and trim angle is correct. Feel out the timing of the ease - too early is better than too late. Don’t get caught overtrimmed as your AW angle returns to optimal or it’s Stall City, USA.

The Wrong Way - Chasing

Poor lull management is common. Mike Ingham uses a great analogy whereby you’re sailing along and imagine the wind dropping instantly and completely - if you chase your apparent wind around, you’ll never actually find good flow, because your AW is all the way forward. You could bear off 150 degrees and your windward telltales will still be luffing - but during that turn, you’re decreasing your AW speed, and you're also pointing further away from your intended goal, destroying VMG. In real-world of gusts and lulls, if you do find an angle that has an acceptable looking flow, you’ll be sailing low and you’ll be slowing down anyway - and will need to head up once you do. Don’t chase your AW, just coast. Simple.

Lulls with Shift Components

Sometimes we have lulls that show up as lifts. In really light air, the wind can die and shift all the time. If that happens, you can sheet out to keep attachment and then change direction to your new optimal angle - don’t go too far though - you don’t want to have to corrective steer back down. When lulls are also true headers, they are treated the same as velocity headers unless we know definitively where the new angle is- so we coast first and then come down after speed has decreased. A good rule of thumb: if your sail is still luffing after about 2 seconds of sailing into a velocity header in light wind, bear away. If you can see the wind direction the water, this will be your best method to determine the actual wind direction and take appropriate action.

These are awesome skills to practice while sailing on your own. Experiment with the different concepts and methods explained here… start thinking more in terms of what your apparent wind does in gusts and lulls. Try to feel your speed increases and decreases. If you’re skeptical, tune-up with a friend and have one of you handle gusts and lulls “The Wrong Way” and one of you practicing “The Right Way” - you’ll see how drastic these gains and losses can be.

This article is part of a four-part series on sailing faster with less hiking. Don't miss Part 1 - Steering and Part 2 - Sail Setup.